Emerging markets have long been a magnet for global capital. The promise is simple: higher growth, higher interest rates, and often, higher returns. Yet for every investor who sees opportunity in Brazil’s bond markets or South Africa’s currency, another recalls the painful lessons of sudden devaluations and capital flight.

One of the most popular strategies in emerging markets is the carry trade—borrowing in a low-interest-rate currency and investing in a higher-yielding one. On paper, it looks straightforward: pocket the spread between borrowing costs and returns. In practice, however, the strategy is shaped by shifting global liquidity, fragile domestic politics, and the ever-present volatility of emerging market currencies.

What Carry Trades Are Really About

At its core, a carry trade is a bet not only on yield differentials but also on stability. Investors borrow cheaply—traditionally in Japanese yen, Swiss francs, or U.S. dollars—and redeploy that capital into higher-yielding currencies. The Brazilian real, Turkish lira, or Mexican peso have all, at different times, been among the favorite destinations.

The attraction is easy to understand. When U.S. or European rates sit near 2–3% and an emerging market central bank sets its benchmark at 8–10%, the arithmetic is irresistible. If the local currency holds steady or even appreciates, the trade pays handsomely.

But exchange rates have a way of humbling even the most sophisticated models. A 5% yield advantage can be wiped out in days if the high-yielding currency slides 15% against the funding currency. This is why carry trades are often described as “picking up pennies in front of a steamroller.”

Why Emerging Markets Tempt Investors

Despite the risks, global capital is drawn to emerging markets for several reasons:

- High yields: Inflationary pressures and higher risk premiums mean EM central banks often maintain much higher rates than their developed counterparts.

- Growth stories: Economies like India, Brazil, or Indonesia offer demographic dividends and expanding middle classes, creating optimism about long-term appreciation.

- Commodity cycles: Oil, copper, soybeans, and gold drive many EM currencies. When commodities rally, so too do local currencies, amplifying carry returns.

In effect, emerging markets promise not just yield but the potential for growth-driven currency gains—making them doubly attractive during good times.

When It Works—and When It Doesn’t

History offers ample examples of both sides of the carry trade story.

- Brazil in the 2000s was a textbook case. The country’s Selic rate was often above 10%, while Japanese rates hovered around zero. Borrowing yen to buy Brazilian real debt became a global favorite. During the commodities boom, when soy and iron ore exports supported a strong real, carry trades delivered spectacular returns. But the 2008 financial crisis brought the party to an end. As global liquidity froze, the real collapsed and leveraged investors were burned.

- Turkey’s lira has repeatedly tempted investors with double-digit yields. Yet chronic inflation, political interference in monetary policy, and persistent current account deficits made the lira a notorious “yield trap.” Many investors discovered that 20% interest rates can be meaningless if the currency loses 30% in value in a year.

- The Taper Tantrum of 2013 showed how vulnerable EM carry trades are to global policy shifts. When the U.S. Federal Reserve hinted it would reduce quantitative easing, capital rushed out of EM currencies like the Indian rupee, Indonesian rupiah, and South African rand. For many, the small yield advantage was no match for the scale of currency depreciation.

These episodes highlight the core truth: carry trades in emerging markets work beautifully during periods of global liquidity and confidence, but they unravel dramatically when sentiment shifts.

The Risks Beneath the Surface

The main danger is currency volatility. But that’s not the only risk. Emerging market carry trades expose investors to a broader set of vulnerabilities:

- Capital flight: EM economies rely heavily on foreign inflows. A shift in global risk appetite can trigger sudden, destabilizing outflows.

- Policy unpredictability: Central banks in emerging economies are not always independent. Political interference can derail policy credibility overnight.

- Liquidity traps: Unlike U.S. Treasuries or German Bunds, EM debt markets can seize up. In times of stress, investors may find themselves unable to exit without steep losses.

- Geopolitical shocks: Elections, sanctions, or conflict can quickly sour sentiment and send currencies tumbling.

In other words, investors in EM carry trades are not just betting on interest rates. They are betting on politics, credibility, and global liquidity—all at once.

The Opportunities Still Matter

Yet it would be a mistake to dismiss carry trades as reckless gambling. Managed carefully, they can provide genuine opportunities. Countries with credible central banks and relatively sound macroeconomic fundamentals remain attractive.

Mexico, for instance, has often stood out in recent years. The Bank of Mexico is respected for its independence and willingness to fight inflation. Proximity to U.S. supply chains has supported the peso, and yields have been consistently higher than in developed markets. As a result, the peso has become one of the more reliable “carry trade” currencies in the current decade.

Brazil, too, continues to attract attention, despite its political ups and downs. Commodity exports and a disciplined central bank have allowed the real to stage repeated comebacks. Meanwhile, South Africa’s rand and Indonesia’s rupiah offer opportunities, but with caveats tied to commodity cycles and structural reforms.

How Investors Approach the Trade

Professional investors rarely treat carry trades as “all-in” bets on a single currency. Instead, they approach them with discipline:

- Diversifying across several EM currencies to avoid overexposure to any one country’s risks.

- Hedging through options or futures contracts to limit the downside of sharp devaluations.

- Sizing positions conservatively, particularly in illiquid currencies where exits can be costly.

- Monitoring global conditions closely, since U.S. interest rate cycles or changes in risk sentiment can upend the trade overnight.

In practice, carry trades are often one component of a broader emerging markets strategy, rather than the whole story.

Broader Implications for Economies

The role of carry trades extends beyond individual portfolios. For the host countries, speculative inflows can have profound effects:

- They can drive currency appreciation, which helps tame inflation but hurts exporters.

- They can fuel rapid credit growth, sometimes sowing the seeds of asset bubbles.

- And when global liquidity tightens, the sudden reversal of carry flows can trigger crises, leaving governments scrambling to stabilize markets.

This dual-edged nature explains why policymakers often view carry trades with ambivalence. They welcome the capital inflows but fear the instability they bring. Some governments resort to capital controls or special taxes to limit speculative inflows, though such measures come with their own costs.

The Landscape in 2025

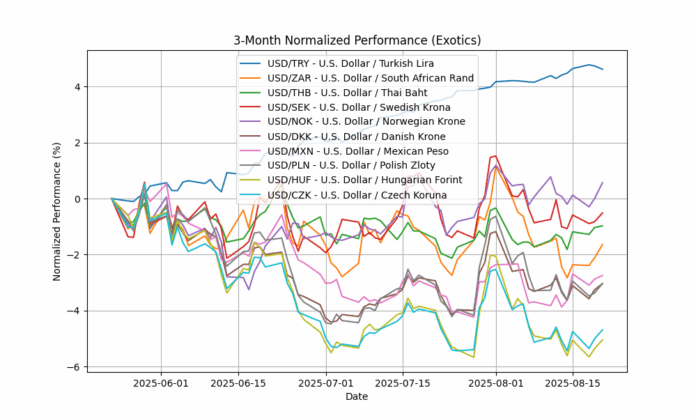

As of today, emerging market carry trades remain alive and well. With interest rate differentials still wide—particularly between the U.S. and countries like Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa—investors are tempted once more. Yet memories of past crises linger, keeping many cautious.

The backdrop is also shifting. Global investors are more attuned to sustainability, governance, and long-term reform. Countries that demonstrate credible monetary policy and fiscal discipline are better positioned to attract stable flows, while those that rely solely on sky-high interest rates without structural reforms risk falling into the “Turkey trap.”

Conclusion

Emerging market carry trades embody the tension at the heart of global investing: the lure of high returns against the fear of sudden loss. They thrive in good times, delivering returns that dwarf what developed markets can offer. But they unravel when currencies wobble, politics intrude, or global liquidity shifts.

For investors, the lesson is caution, discipline, and diversification. For emerging economies, the challenge is to harness foreign inflows without becoming hostage to them.

In the end, carry trades are neither miracle machines nor reckless gambles—they are a reflection of the broader dynamics of global finance. They remind us that in emerging markets, opportunity and risk are inseparable companions.